[동아시아포럼] 남중국해 긴장 완화를 위한 과학외교 전략

러-우크라 전쟁 이후 중국의 대만 침공 가능성 제기 중국·대만·베트남 등 남중국해 주변 영토 분쟁 심화 천연자원 보고로 환경문제 등 연안국 공동대응 필요

[동아시아포럼]은 EAST ASIA FORUM에서 전하는 동아시아 정책 동향을 담았습니다. EAST ASIA FORUM은 오스트레일리아 국립대학교(Australia National University) 크로퍼드 공공정책대학(Crawford School of Public Policy) 산하의 공공정책과 관련된 정치, 경제, 비즈니스, 법률, 안보, 국제관계에 대한 연구·분석 플랫폼입니다. 저희 폴리시코리아(The Policy Korea)와 영어 원문 공개 조건으로 콘텐츠 제휴가 진행 중입니다.

중국, 대만, 베트남, 필리핀, 말레이시아, 브루나이 등 6개국으로 둘러싸여 있는 남중국해는 오랜 기간 영토 분쟁과 해양통제권을 두고 주변국 간의 긴장과 갈등이 이어져 왔다. 하지만 최근 각국 정부는 경제적 안정, 환경 문제 등 공동의 이슈에 대응하기 위해 과학기술 협력사업을 추진함으로써 남중국해의 긴장을 완화하고 국가 간 관계를 개선하기 위해 노력하고 있다.

남중국해 군사기지화 우려 및 양안 전쟁 가능성

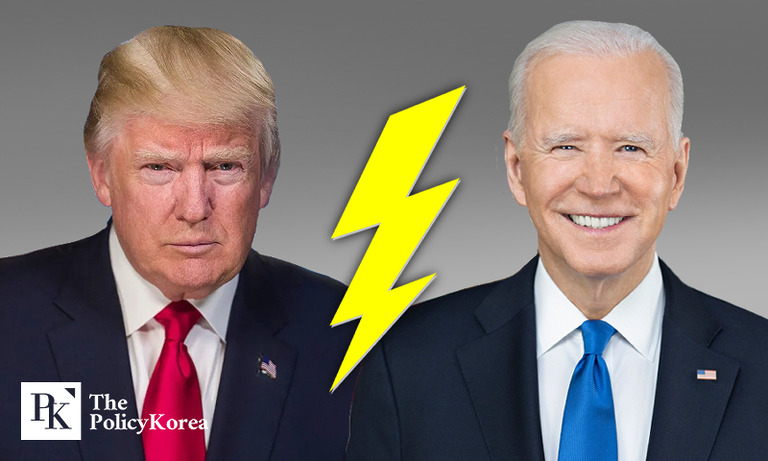

지난해 2월 러시아의 우크라이나 침공 이후 중국의 대만 침공 가능성이 제기되면서 미국 등 주요국 전문가들은 다양한 가상 시나리오들을 내놓으며 남중국해의 긴장에 대해 우려를 제기했다. 이같은 우려는 올해 8월 중국 해안경비대가 필리핀의 재보급 호송대에 물대포를 발사하자 더 강화됐다.

남중국해는 천연자원과 물류의 전략적 요충지로, 이 지역의 영토주권을 두고 오랜 기간 중국, 대만 등 주변국 간의 갈등이 이어지고 있다. 여기에 남중국해의 군사기지화를 우려하는 미국 등 주요국들이 개입하며 국제정세에 주요한 영향을 미치고 있다. 일반적으로 영토주권은 유엔(UN) 등 관련 국제기구의 승인을 통해 인정받으며 이를 통해 배타적 경제수역(Economic Exclusion Zone, EZZ)을 확보하고 해당 지역의 방대한 어류를 포획·채취·수확할 수 있다. 남중국해는 전 세계 어획량의 12%를 차지하는 등 세계 주요 어장 중 하나로 연안국들의 어업에서 중대한 가치가 가진다. 또한 110억 배럴의 원유, 5조4,000억㎥의 천연가스가 매장된 에너지 자원의 보고이자 전 세계 해운 물류의 1/3이 통화하는 물류의 요충지다.

남중국해를 둘러싼 갈등이 장기화되면서 중국, 베트남, 필리핀 등 연안국들은 물론 아세안(ASEAN·동남아시아국가연합) 등 아시아·태평양 지역 국가들은 지역의 긴장 완화와 안정 유지를 위해 노력하고 있다. 남중국해 인근 국가의 전문가를 대상으로 실시한 설문조사에서 응답자들은 지역의 갈등과 긴장을 개선하기 위한 방안으로 양자 간 과학기술 협력이 효과적인 전략이 될 수 있다고 제안했다. 이들은 베트남, 필리핀 등 동남아시아 국가들과 중국 간 영토 분쟁을 남중국해의 주요한 위기 요인으로 꼽으면서도 해양자원의 개발, 국가 간 경쟁, 멸종위기 어류의 남획, 환경 파괴 등과 같은 경제적·환경적 문제가 지역의 위기를 촉발하는 또 다른 요인이 될 가능성이 있다고 응답했다.

中 군사적 도발에 국가 간 갈등 심화, 과학외교 중요성 증대

중국은 남중국해를 자국의 군사기지로 만들기 위해 주변국의 EEZ를 침범하고 불법적으로 해양 자원을 채취하는 등 지역의 긴장을 촉발시키고 있다. 중국은 이 지역 자원에 대한 소유권을 넘어 남중국해의 섬들을 자국의 영토라고 주장하면서 항공기, 미사일, 해군 함정과 같은 대형 군사 자산을 설치·유지하기 위해 인근의 섬과 암초를 개발해 인공섬을 건설했다. 이같은 중국의 군사적 도발에 베트남도 맞불을 놓으며 강하게 대응하고 있다. 최근 베트남은 중국을 견제하기 위해 베트남이 실효 지배 중인 도서에서 군사시설을 확충하겠다고 밝혔다.

이렇게 국가 간 긴장이 심화되는 상황일수록 과학외교의 역할이 중요하다. 양자 간 과학외교는 객관적이고 과학적인 분석을 토대로 정책을 수립하고 의사결정을 하는 증거기반 외교 원칙을 준수함으로써 지역의 안정과 대화를 촉진하는 최선의 방책이다.

불법적 어업활동과 남획, 수온 상승으로 인한 산호 백화 등의 문제는 남중국해의 환경과 경제 활기를 훼손할 수 있는 중대한 사안임에도 그동안 지정학적 갈등으로 이같은 공동의 문제들이 개별 국가 차원에서 분절적으로 다뤄졌기 때문에 효과적인 개선책을 모색하는 데 한계가 있었다. 이런 상황에서 과학기술에 기반한 신뢰 구축은 장기적으로 지정학적 긴장을 완화하는 것은 물론, 광범위한 협력의 토대가 된다. 남중국해 연안국을 비롯해 양자 간의 과학기술 협력은 이전에도 있었다. 지난 1994년 필리핀과 베트남이 과학 연구협정을 체결했고, 최근 군사적 갈등이 격화되고 있는 중국과 베트남도 이미 지난 2004년 어업, 탄화수소 추출, 해양안보 분야의 협력을 담은 통킨만 어업협정을 체결한 바 있다.

남중국해의 과학외교는 다자간 아닌 ‘양자 협정방식’ 채택해야

과학외교에서 다자간 협정 방식을 채택하는 경우도 있지만, 남중국해의 경우 포괄적이고 강제적인 다자간 프레임워크는 적절하지 않을 것으로 보인다. 남중국해 분쟁의 당사국들 모두 UN해양법협약(UNCLOS)에 서명했음에도 영토 분쟁에서 자국의 목표를 달성하기 위해 이를 준수하지 않기 때문이다. UNCLOS는 영해·EEZ·공해·심해저 제도 등에 대한 해양관할권, 해양자원과 생태계 보전, 관련 기술의 개발·이전 등을 규정하며 분쟁의 조정에 있어 구속력을 수반하는 강제절차를 포함한다. 이번 설문조사에 참여한 전문가 대다수도 남중국해의 과학외교는 남극 조약 같은 다자간 프레임워크를 채택하는 것이 적절하지 않다고 응답했다. 남중국해를 둘러싼 주요국의 이해관계, 천연자원의 매장량이나 활용 가능성 등을 고려할 때 다자간 협정을 통해 긴장을 완화할 가능성은 높지 않다는 이유에서다.

다만 양자 외교는 개별 협정이나 외교정책에 있어 각국의 영향력이 크기 때문에 이들의 관계가 악화될 경우 국제정세에도 부정적인 영향을 미칠 위험이 있다. 실제 그간 중국은 남중국해의 영토 분쟁에서 복수의 국가들이 상호 연대해 공동 대응하지 못하도록 하기 위해 아세안 회원국과의 양자 협상을 고수해 왔다. 이에 관련 국가들은 양자 간 과학외교를 추진하면서도 당사국 간의 균형을 유지함으로써 자국의 영토주권을 훼손하지 않도록 유의할 필요가 있다. 남중국해에서의 양자 간 과학외교가 기존의 영토 분쟁을 해결하거나 아세안 등 지역 회의체에 과학적인 기여를 할 가능성은 낮다. 하지만 국가 간 대화를 확대해 긴장을 완화하는 전략으로는 매우 가치 있으며 결과적으로 충분한 협력이 이뤄진다면 남중국해의 환경 문제를 해결하는 데도 도움이 될 것으로 보인다.

원문의 저자는 데이비드 헤센(David Hessen) 남중국해 뉴스와이어(South China Sea NewsWire) 편집장입니다.

Scientific collaboration could ease tensions in the South China Sea

The South China Sea region has long been home to tensions driven by disputes over territory and control over resources. Local policymakers should respond by reinforcing bilateral relationships along the basis of scientific cooperation. A new survey suggests a path towards de-escalation built upon nations’ shared concern for regional economic stability and environmental stewardship.

Taiwan and the crisis of international stability that would be brought on by a hypothetical Chinese invasion have captured significant attention. While this attention is rightly deserved, territorial and economic disputes in the South China Sea are no less noteworthy given their potential impact on regional and global stability.

This importance was reinforced in August 2023 when a Chinese Coast Guard vessel intercepted a Philippines resupply mission to one of the disputed South China Sea islands. Attempts to reduce tensions in the South China Sea should be a priority for the various claimants, which include China, Vietnam and the Philippines.

A survey of South China Sea professionals and academics offers a potential avenue to do just that. The survey suggests that tackling shared environmental threats through increased bilateral scientific cooperation might be a promising path forward.

While most of the regional experts interviewed consider the territorial disputes between China and its Southeast Asian neighbours to be the primary issue of concern, the overwhelming majority of survey participants also agree that there are significant economic and environmental concerns exacerbating these disputes.

The South China Sea is a major fishing ground for many states, accounting for nearly 12 per cent of fish caught globally. International recognition of territorial control of certain geographic features permits a state to claim the accompanying economic exclusion zone and harvest vast quantities of food. The region is also home to an estimated 11 billion barrels of untapped oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas. The South China Sea is a critical trade lane as well, with one third of global shipping passing through the region.

China is the greatest violator of economic exclusion zones and the largest contributor to militarisation and illegal resource extraction within the region. Beyond claiming economic ownership of the region’s resources, China asserts that the islands of the South China Sea are Chinese territory and has built up islands and reefs to sustain large-scale military assets such as aircraft, missiles and naval vessels.

But China is not the only participant militarising the region. Vietnam’s reported plans to fortify its existing military installations in the South China Sea make scientific diplomacy more vital than ever.

Bilateral scientific diplomacy — the direct support of foreign policy processes through scientific advice and evidence — offers the best course of action for ensuring regional stability. Issues such as overfishing, coral bleaching and pollution all stand to cripple the region’s environmental health and economic vitality. Geopolitical competition has ensured that these regional threats have only been addressed on a piecemeal and state-by-state basis. Building trust and science-based relations has the potential to reduce these tensions over time and build a framework for broader cooperation.

The idea of bilateral scientific cooperation between South China Sea claimants is not new. The Philippines and Vietnam have a scientific research agreement in place that dates back to 1994. Even direct rivals China and Vietnam abide by the 2004 Gulf of Tonkin Agreement, which established cooperation in fishing, hydrocarbon extraction and maritime security.

While scientific multilateral agreements do exist, this method is unlikely to establish a comprehensive and obligatory multilateral framework for conflict resolution in the South China Sea. All parties to South China Sea disputes are signatories of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea — a supposedly binding agreement on naval rights and environmental responsibilities — but the parties have not succeeded in adhering to a regional framework to accomplish these goals because of their territorial disputes.

A significant majority of the survey participants reject regional frameworks like the Antarctic Treaty as a model for scientific collaboration and diplomatic engagement in the South China Sea. Although Antarctica is also no stranger to territorial disputes, the South China Sea’s proximity to regional powers and the greater extractive potential of its natural resources makes the successful reduction of tensions through multilateral agreement — scientific or not — less likely.

Bilateral diplomacy does have risks of its own by increasing the individual leverage of any state upon mutual policy. China has advocated for bilateral negotiations with ASEAN states to ’divide and rule’ the organisation and prevent a unified regional response to its territorial claims. Although this a legitimate concern, multilateral agreements are unlikely to form or to ensure de-escalation. Regional states must carefully pursue bilateral science diplomacy to de-escalate tensions while not permitting these relationships to become one-sided and detrimental to their sovereignty.

While a web of bilateral scientific relationships will not resolve existing territorial disputes in the South China Sea nor provide the potential for scientific advancement that a regional forum would, all potential methods of opening communication and reducing tensions in the region are worth exploring. And with enough scientific cooperation, the region’s environmental health just might improve too.