[동아시아포럼] 일본산 해산물 수입 금지로 보여준 중국의 외교 전략 미숙성

중국, 과학적 분석 결과 무시하고 8월부터 일본산 해산물 수입 금지 조치 발동 실상은 한-미-일 3국의 안보 협력에 대한 불만, 대만 해협 주도권 확보 대내적으로는 경기 침체에 대한 불만 타개, 대외적으로는 태도국들과의 연합 목적

[동아시아포럼]은 EAST ASIA FORUM에서 전하는 동아시아 정책 동향을 담았습니다. EAST ASIA FORUM은 오스트레일리아 국립대학교(Australia National University) 크로퍼드 공공정책대학(Crawford School of Public Policy) 산하의 공공정책과 관련된 정치, 경제, 비즈니스, 법률, 안보, 국제관계에 대한 연구·분석 플랫폼입니다. 저희 폴리시코리아(The Policy Korea)와 영어 원문 공개 조건으로 콘텐츠 제휴가 진행 중입니다.

지난 8월 24일 일본 정부가 후쿠시마 원전 처리수를 태평양 앞바다에 방류하자 중국 정부는 즉각 일본산 해산물 수입 금지를 선언했다. 민간의 수산물 안전에 대한 우려가 그 이유기는 하나, 그간 일본 정부가 보여준 국제 안전 기준에 대한 이해 및 적용 의지, 중국 정부의 책임 부인 행태, 중국 원전의 오염수 방수 사건 등을 감안할 때 중국의 숨겨진 의도가 무엇인지를 살펴볼 필요가 대두된다.

중국, 일본 후쿠시마 오염 처리수 방류 시작하자 해산물 수입 금지령 선포

이번 수입 금지 조치는 중국 관세청이 발표한 것으로 허위 정보 확산에 따른 피해를 막기 위한 것이라는 설명이 있었음에도 불구하고 실질적으로는 일본에 대한 정치적인 의도가 깔려있었을 것이라는 해석이 지배적이다. 특히 일본이 그간 한국 및 미국과 안보 협력을 강화해 온 것에 대한 보복 조치라는 것이 관계자들의 해석이다.

외교가에서는 금지 조치가 대내외적인 신호 효과가 있을 것으로 예상한다. 중국 국내 상황에서는 경기 침체로부터 시야를 돌려 반(反)일본주의로 대중을 선동하겠다는 목적을 짚을 수 있고, 대외적으로는 태평양도서국가(태도국)들의 우려를 들어주는 강대국으로 자리매김해 ‘약소국 응원 국가’라는 그간의 중국 외교 정책과 맞닿아 있는 외교적 선택이라는 것이다.

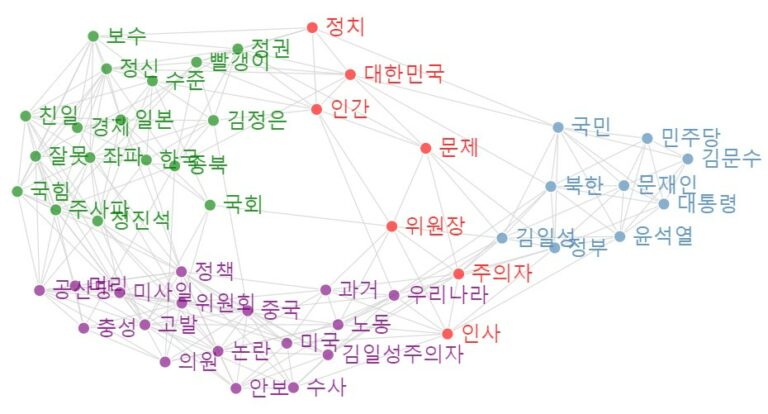

중국은 그간 수출·수입을 외교 전략의 무기로 삼아왔다. 일본은 지난 2010년 동지나해 일대의 센카쿠 열도(중국명 댜오위다오) 분쟁 문제로 말미암아 주요 광물 수출 금지를 맞은 바 있다. 2017년에는 한국이 미국과 미사일 방호조약(THADD)을 체결하자 보복 조치로 한국 상품 및 서비스 수입을 금지했으며, 이어 호주에서 코로나19의 출처가 어디냐에 대한 독립 기관의 요청이 있자 호주 상품 수입에 대한 금지를 지정하기도 했다.

중국은 이번 해산물 수입 금지령을 세계무역기구(WTO)의 위생검역조치의 일환이라는 이유로 정당화했다. 그러나 중국 내부의 보고서에 따르면 중국 정부가 허위 정보 확산에 일조했다는 것이 알려져 논란이 되고 있다. 정부 산하의 미디어 기관이 핵물질의 안정성에 대한 과학적 근거 자료를 무시하는 발표를 내놨고, 심지어는 홍보를 위해 서비스 비용을 지불한 사실도 함께 알려졌다.

일본뿐만 아니라 한국·미국과도 외교적 결별 시사

이번 수입 금지령이 관세청에서 나온 만큼, 단순히 과학적 근거자료나 부정확한 정보 확산에 대한 우려를 넘어 사실상 중국 당국이 움직였다고 보는 것이 옳다는 지적도 나온다. 그러나 중국의 의도가 일본의 태도 변화였다면 해산물 수입 금지령은 큰 의미가 없다는 분석이다. 양국 간 전체 교역량의 일부분에 지나지 않기 때문이다.

외교 전문가들은 이번 금지령이 상징적인 의미를 담고 있는 가운데, 정책적으로는 크게 두 가지 목표를 갖고 있을 것으로 해석한다. 첫째, 금지령 선포 1주일 전 한·미·일 3국 정상이 워싱턴에서 모여 3자 정상회담을 가진 것을 지적한다. 3자 간 안보 협력 강화를 약속한 가운데 대만 해협의 불안정성을 깨기 위한 노력이 합의 중 일부였다는 해석이 나오는 만큼, 중국 입장에서는 남중국해 일대에서 중국의 역할을 약화시키는 계기가 될 수 있다는 것이다. 중국은 실제로 3자 회담을 비난하며 자세한 논평을 피했다. 따라서 이번 금지령은 중국이 일본에 압박을 가하면서 실질적인 책임을 회피하는 전략이라는 해석이 가능하다.

두 번째는 ‘미덕 신호(Virtue signalling)’다. 최근 중국이 대내적으로 미증유의 청년 실업, 부동산 경기 침체, 경제 성장률 감소 등으로 어려움을 겪고 있는 만큼, 외부의 고난을 함께 이겨낸다는 이미지를 제공하는 것이 중국 국민들의 감정을 다스리는 데 효과가 있을 것이라는 기대가 그것이다. 국수주의적인 관점을 상기시켜 과거의 적국이었던 일본에 대한 불만을 고조시킬 경우 최근의 경제적 어려움에서 눈을 돌리게 만들 수 있다는 기대감이 깔려있다는 뜻이다.

한·미·일 연합과 중국-태평양도서국 연합으로 갈라진 서태평양 정세

국제적으로 이번 금지령은 태도국들에 대한 지지로도 해석될 수 있다. 일찍이 태도국들은 일본의 오염 처리수 방류가 자연환경에 심각한 피해를 줄 수 있다는 경고를 내놓은 바 있으나 국제적인 협력은 부족한 상황이었다. 이런 가운데 중국이 일본의 방류에 대한 우려를 함께 표명해 주면서 태도국들의 발언에 힘이 실리게 됐다는 것이다. 실제로 솔로몬제도의 머내시 소가바레(Manasseh Sogavare) 총리는 일본의 방류를 강하게 비난했으며, 피지제도에서는 여러 차례 반대 시위가 열리기도 했다. 중국은 뒤에서 태도국들을 지원하는 모양새다.

최근 미-중 갈등이 고조되면서 다양한 지정학적 도구들을 활용하는 등 서로 간 견제가 심화하고 있다. 한·미·일 3국 협력은 중국을 압박하기 위해 꺼내든 미국 조 바이든 대통령의 여러 전략 중 일부에 불과하다. 미국이 한국, 일본과 협력을 강화하면서 중국도 그에 맞서 태도국들과의 연합으로 외교적 고립을 타개하려는 것으로 해석할 수 있다. 이번 수입 금지령은 중국이 과학적 근거 자료와 관계없이 자국의 이익이 침해될 경우 언제든지 수출, 수입 제재와 같은 외교적인 수단을 꺼낼 수 있다는 증거라는 해석도 나온다.

원문의 저자는 호주국립대학(ANU)의 안보 전문대학 연구원인 월터 브레노 콜나기(Walter Brenno Colnaghi)입니다.

Japanese seafood ban signals China’s shady virtues

On 24 August 2023, immediately after Japanese authorities released treated wastewater from the Fukushima nuclear plant into the Pacific Ocean, China suspended all seafood imports from Japan. While the public’s concerns over contamination might justify the decision, China’s track record of employing plausible deniability, coupled with Japan’s compliance with international safety standards and China’s similar nuclear waste management practices, raise questions about China’s motivations.

The restriction was issued by the General Administration of Customs and followed a protracted disinformation campaign aimed at stoking public fears, suggesting that political motivations lie behind the decision. The episode offered a pretext for Beijing to punish Tokyo’s push to increase security cooperation with Seoul and Washington.

It also allowed China to send signals to both domestic and international audiences. Domestically, Beijing stoked anti-Japanese sentiments to divert attention from a troubled economy. Internationally, China echoed concerns aired by Pacific Island nations to reiterate its image as champion of the ‘Global South’.

China has become adept at using trade as a tool of statecraft. Japan suffered export bans for critical minerals in 2010 amid heightened territorial tensions in the East China Sea. In 2017, Beijing embargoed South Korean goods and services after Seoul deployed US anti-missile batteries. China also imposed informal sanctions over a range of Australian products following Canberra’s call for an independent inquiry into the origins of COVID-19. China leverages its huge market and dominance over critical supply chains to punish unwanted behaviour.

China justified the seafood ban by invoking the World Trade Organization’s rules on phytosanitary measures. Yet reports in China exposed a government-coordinated disinformation campaign on the issue. State-owned media discredited scientific advice endorsing the release of nuclear wastewaters with paid social media campaigns and misleading reporting. Japanese schools, businesses and diplomatic missions in China were harassed. The ban being issued by the General Administration of Customs suggests that the order came from the top down, rather than being the result of lower-level technical bodies’ decisions snowballing into a national policy.

But if Beijing’s intention was to alter Tokyo’s behaviour, seafood is not an effective economic stick, since it makes up only a marginal component of bilateral trade. The ban mainly risks affecting Chinese companies, as consumers have already stopped buying seafood altogether.

The ban is largely symbolic, and the rationale may be twofold. The week prior to the ban, leaders from Japan, South Korea and the United States gathered in Washington to elevate trilateral cooperation. The parties agreed to deepen trilateral defence cooperation, endeavour to tackle instability in the Taiwan Strait and the broader Indo-Pacific and condemned China’s conduct in the South China Sea. Unsurprisingly, the summit prompted China’s condemnation but excluded explicit countermeasures. The Fukushima case provided Beijing with an opportunity to chastise Tokyo while maintaining plausible deniability about its political intentions and not stirring up further tensions.

Beijing may have another reason for banning Japanese seafood — virtue signalling. At home, China is grappling with unprecedented youth unemployment, a stumbling property sector and decreasing growth rates. Appeals to endure hardship can only do so much to mobilise support from a disillusioned population. Stirring nationalistic sentiments against the old enemy Japan through disinformation and the trade ban provided the Chinese government with a useful decoy to temporarily distract the domestic audience from economic troubles.

Internationally, the ban is aimed at signalling support for the South Pacific’s concerns. China’s concerns over the discharge of the Fukushima waters echo Pacific Island nations’ reservations, as they more strongly perceive the dangers of contamination. Solomon Islands Prime Minister Manasseh Sogavare strongly condemned Japan’s actions and protests took place in Fiji. Beijing acted as the bellwether of the South Pacific nations, throwing weight behind their claims to curry favour with states in the increasingly contested region.

As the US–China rivalry intensifies, adversaries will use every opportunity to accuse the other of playing geopolitics. The strengthening of the US–Japan–South Korea trilateral cooperation is only one recent example of US President Joe Biden’s goal of strengthening the ‘latticework’ of alliances to shape China’s behaviour. As the United States doubles down on its allies, Beijing has looked to intensify its outreach to the Global South, labelling Washington’s alliances forms of containment.

China’s move is a signal against the United States and its allies — most of whom supported the waters’ discharge — that Beijing has no qualms about questioning scientific evidence to accuse them of misconduct. It also sends a message to the whole region that, should tensions intensify, China will not hesitate to dial up the pressure. The Fukushima case shows that trade and economic linkages will be exploited as tools of statecraft more and more frequently.